When I first worked with the University of Alberta Museums’ teaching collection, I expected clinical curiosity. I didn’t expect a syphilitic brain in a stainless-steel tray (or a cancerous vulva preserved in formalin) staring back at me. Or seeing the soft fontanels of a dozen preserved fetal skulls organized neatly in a row.

Fascination quickly collided with unease: these weren’t just specimens; they were people.

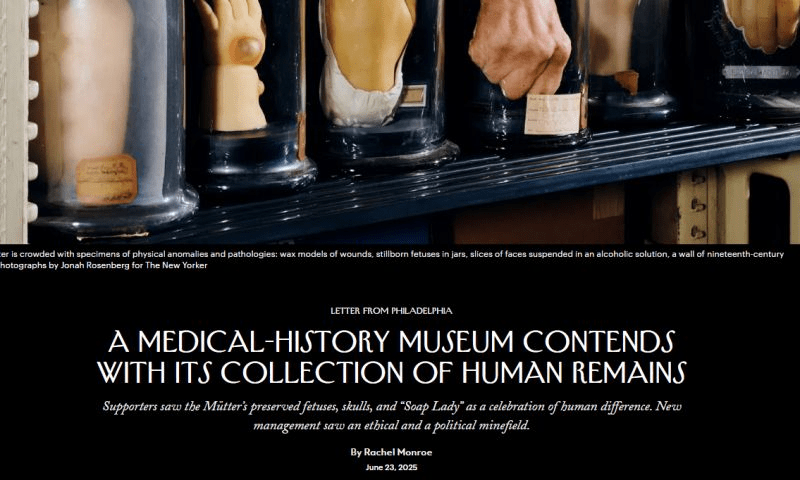

Rachel Monroe’s recent article in The New Yorker, The Mütter Museum’s reckoning picks up the same thread on a bigger stage. New leadership paused “edutainment” videos and began auditing thousands of historic remains, only to discover that “much, much less than two or three per cent” were obtained with clear consent. Meanwhile, critics warned that removing jars from display would erase a hard-won medical archive.

Here’s the paradox every pathology collection faces:

• Modern medicine still needs end-stage examples. We rarely allow diseases to “run their course,” so preserved tissues remain invaluable teaching tools.

• Provenance can be murky or outright exploitative. Many 19th-century acquisitions rode roughshod over class, race, and colonial power dynamics

So where’s the balance? My take:

• Context ≠ Censorship. Transparency about how, why, and from whom specimens were taken transforms gawking into learning.

• Shared Stewardship. Descendant or stakeholder input should guide display decisions, not just institutional tradition.

• Dynamic Interpretation. Ethical labels and digital surrogates can sit beside original material, not automatically replace it—Monroe calls this Mütter’s emerging “secret third way.”

I’m curious to know how fellow curators, health sciences educators, and heritage professionals are navigating this tightrope. How do you decide when a jar stays on the shelf, and when it belongs back in the ground?

From Edmonton to Philadelphia: What a Syphilitic Brain Taught Me About Museum Ethics

Time to Read:

1–2 minutes

Leave a comment