A reflection on economic logic, policy language, and what we refuse to name

Arts and culture are already an economic sector.

Not metaphorically. Not aspirationally. Measurably.

According to Business for the Arts’ Artworks: The Economic and Social Dividends from Canada’s Arts and Culture Sector, Canada’s arts and culture sector directly contributed $65 billion to the economy in 2024, accounting for 2% of national GDP. When indirect and induced impacts are included, the sector supported $131 billion in total economic activity and over 1.1 million jobs.

The sector’s impact is not symbolic.

It’s industrial scale.

And yet, a recent Hill Times article warned that Canada is actively missing economic and geopolitical opportunities by continuing to underinvest in the arts sector. Cultural organizations argue that federal policy still treats culture as discretionary spending, despite its proven role in export development, job creation, and international influence (The Hill Times, 2026).

The article frames culture as a strategic asset: one that generates measurable economic return while simultaneously advancing Canada’s global reputation and soft power. By failing to treat it as such, Ottawa is not being cautious. It is being strategically timid.

Framing matters because it tells us this is no longer a debate about value.

It is a debate about political will.

Our policy language still treats culture as discretionary.

As enrichment.

As “nice, if affordable.”

That is the contradiction.

This is not a story about culture being meaningful.

It is a story about how we govern things we refuse to fully recognize.

The Dissonance: What Governments Say They Believe vs What Budgets Actually Reveal

Governments say they want:

- Economic diversification

- Export growth

- Global competitiveness

- Cultural diplomacy

- Regional development

- Creative innovation

But their funding behaviour tells a different story:

- Declining share of federal expenditures

- Episodic investment

- Precarity as a business model

- Culture is treated as cost containment

We want culture to perform like an industry while funding it like a courtesy.

That is not fiscal restraint; that is incoherence.

The Evidence Is Already In

The 2025 Canadian Chamber of Commerce Artworks report is explicit:

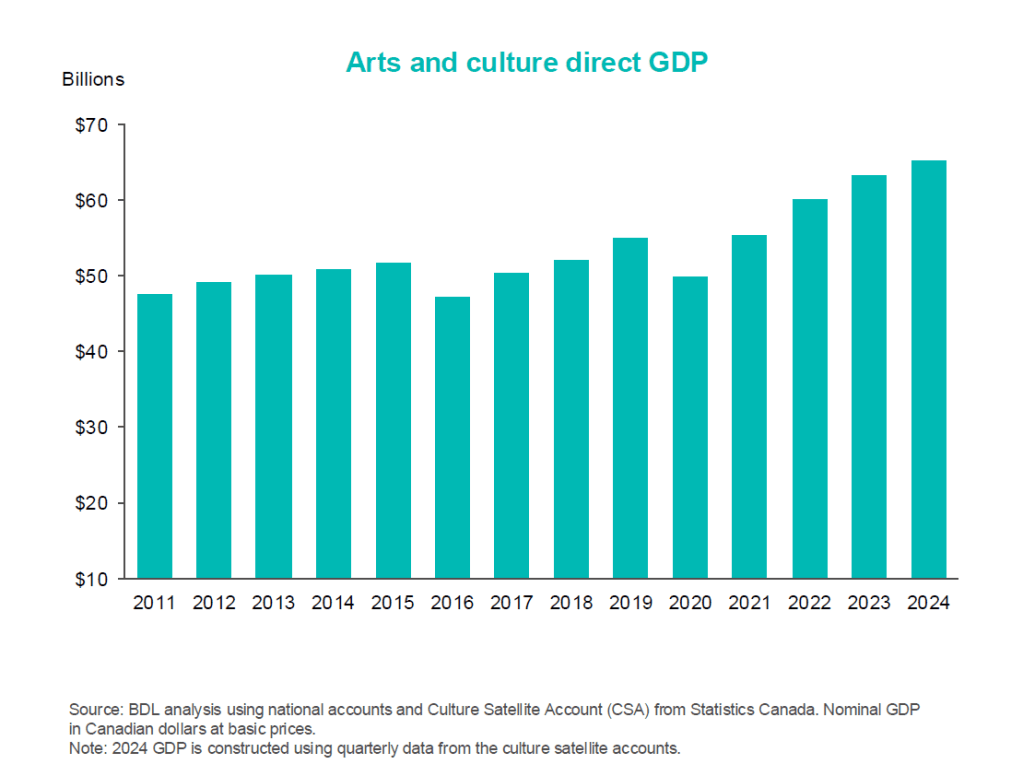

Following nearly a decade of stagnation, Canada’s arts and culture sector has added nearly $10 billion in direct GDP since 2021, surpassing pre-pandemic levels.

Over the past three years, the sector grew by almost 8%, compared to 4% growth for the overall Canadian economy.

And over the long term, arts and culture have outpaced growth in key sectors, including oil and gas, wholesale trade, retail trade, construction, and manufacturing, since 2011.

Read that again, particularly in jurisdictions where oil and gas are still framed as the primary economic drivers. Arts and culture have outpaced growth in oil and gas, wholesale and retail trade, construction, and manufacturing for over a decade.

Arts and culture are not “nice to haves”; they are a core economic driver across the country.

Culture is growing faster than sectors we reflexively call “core industries.” Yet it is still managed as marginal…

The data are clear: this is a governance problem.

Scale Changes Responsibility

The report also shows that arts and culture generate substantial public revenue. In 2024, the sector contributed approximately $16.5 billion in federal and provincial tax revenues through personal and corporate taxation.

This is not a sector that “requires” government.

It is a sector that offers returns on investment to the government.

And yet, we continue to structure funding as if culture were a liability rather than an asset.

This Is Not About Passion. It Is About Infrastructure.

Industries do not scale on inspiration alone. They scale on:

- Capital

- Policy coherence

- Market access

- Export infrastructure

- Predictable financing

We already grant this logic to manufacturing, energy, and technology.

We simply refuse to apply it to culture.

Precarity does not produce competitiveness.

Stability does.

The System-Level Contradiction

We publicly acknowledge culture’s contribution to GDP, yet continue to constrain the capital required for its sustainability and growth.

We celebrate evidence of sectoral expansion while withholding the infrastructure needed to support it.

We articulate expectations of export readiness, but fail to provide the market development mechanisms that such readiness presupposes.

What is particularly revealing is that the financial tools to address these gaps already exist. They are widely used across for-profit and social enterprise ecosystems: patient capital, growth financing, blended finance models, repayable contributions, revenue-based financing, and impact investment instruments that recognize long-term value rather than short-term return. These tools are routinely deployed in technology, clean energy, agriculture, and social innovation sectors to stabilize early growth, absorb risk, and enable scale.

Culture is largely excluded from this landscape.

Instead, it remains governed almost exclusively through short-term grants and project-based funding models that are structurally incapable of supporting capitalization, asset building, or long-horizon growth. This is not because culture lacks economic performance, but because its financial architecture has never been permitted to evolve beyond a charitable paradigm.

Over time, this creates more than a funding problem.

It creates an identity problem.

The language of “nonprofit” becomes internalized as a ceiling on ambition, a rationale for scarcity, and a moral framing that equates financial restraint with artistic integrity. What emerges is a culture of self-imposed austerity, justified in the name of purity: for the good of the art, for the protection of the mission, for the avoidance of “commercialization.”

But austerity is not neutral.

It is a structural position.

When a sector accepts chronic undercapitalization as ethical, it teaches governments and industry to treat it as economically marginal. More troublingly, it teaches the sector to treat itself as such.

We do not merely receive diminished investment.

We normalize deserving less.

In no other major economic sector is undercapitalization reframed as virtue.

In no other industry is fragility mistaken for authenticity.

And yet in culture, scarcity is often moralized.

This is our philosophical inheritance.

objections we keep hearing

Usually, the resistance sounds like this:

- “Arts funding isn’t essential infrastructure.”

- “Culture should be market-driven if it’s truly valuable.”

- “Public money should prioritize healthcare, housing, and energy.”

These concerns sound reasonable until we apply them consistently.

We do not ask transportation to fund itself before being called infrastructure.

We do not require clean energy to be profitable before being strategic.

We do not tell manufacturing to survive on passion.

The issue is selective economic legitimacy.

My Lens

I work inside cultural systems. I design strategies, advise on governance, and help institutions translate values into operational reality. I watch governments celebrate culture’s impact while designing policies that keep it structurally fragile. I see a fear of making any significant investment in historical and cultural assets, while other sectors (e.g., sport tourism) receive substantial government subsidies. The contrast is visible in real time: tens of millions committed to sports infrastructure, while cultural infrastructure is asked to survive on incremental, short-term funding. I have worked with heritage buildings, museums, and cultural centres that are tasked with preserving nationally significant assets, with budgets smaller than the contingency line for a single sports facility project. The message is not subtle: culture expects gratitude for survival, not support for growth.

I also watch institutions internalize this fragility. I see organizations manage decline as responsibility, confuse sustainability with survival, and equate financial ambition with mission drift.

I see culture asked to perform like an industry while being financed as if it were a hobby.

This is our philosophical failure.

It reflects a deeper uncertainty about whether culture is permitted to be powerful, capitalized, and economically self-determining.

Until that question is resolved, no funding model will ever be sufficient.

Final Thought

If governments were serious about treating culture as infrastructure, they would:

- Integrate culture into economic development, trade, and export strategies

- Develop capitalization tools beyond grants: loan guarantees, patient capital, and revenue-based financing

- Fund cultural infrastructure with the same seriousness as sport, tourism, and transportation

- Measure success in stability and scale, not survival

If institutions were serious, they would:

- Stop equating scarcity with virtue

- Build financial literacy alongside artistic excellence

- Demand funding models that allow growth, not just continuity

If individuals were serious, they would

- Stop apologizing for culture’s economic value

- Stop minimizing its labour

- Stop treating financial ambition as a betrayal of mission

Eventually, every economy must decide what it believes culture actually is.

Decoration.

Or infrastructure.

Right now, Canada is still trying to live in both stories at once.

References

Canadian Chamber of Commerce (2025). Artworks: The economic and social dividends from Canada’s arts and culture sector.

CBC News. (2023). Smith government supports Flames arena with $39 million. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/smith-government-flames-arena-39-million-1.6954672

Legree, D. (2026, January 10). Feds missing out on economic, geopolitical opportunities by not supporting arts sector, say cultural groups. The Hill Times.

Statistics Canada. Culture Satellite Account (CSA).

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. (2025, October 28). Alternative Federal Budget 2026: Arts and culture.

Leave a comment